This story was originally published by The Wichita Beacon, an online news outlet focused on local, in-depth journalism in the public interest.

By Polly Basore Wenzl, The Wichita Beacon

What does youth fentanyl overdose look like? In Sedgwick County it often looks like parents finding their teenager dead in bed — or a toddler dead on the floor, fentanyl pills scattered next to him.

That’s not supposed to happen. Parents expect kids at home to be safe, not at risk of the No. 1 killer of teens — car accidents — or other things parents worry about, like gun violence or sexual assault.

But increasingly it is happening. Young people are accidentally overdosing, often at home, on a drug so powerful just one pill can kill. With the numbers climbing each year, youth and adults in the Wichita area are working hard to make these deaths stop.

It’s not a simple problem to solve.

Fentanyl – the killer hiding in fake pills sold on the street

Fentanyl is a potent opioid —50 to 100 times stronger than morphine. Its legitimate purpose is to treat pain in cancer patients and following surgery. Because of its potency and low cost to produce, illegally manufactured fentanyl is often cut into other drugs.

It frequently shows up in fake Percocet pills sold by street dealers. The DEA estimates that six in 10 fake Percocet pills contain fatal levels of fentanyl. When a person ingests a lethal amount of fentanyl, their breathing may slow and cause hypoxia, a condition that can lead to brain damage and death.

Coroners’ reports are increasingly identifying fentanyl toxicity as a killer of both adults and children. The rate of deaths has been rising so rapidly that last year community leaders, law enforcement and local schools began sounding the alarm in town halls and through public awareness campaigns.

But no one has publicly quantified local youth fentanyl death — until now.

Sedgwick County Regional Forensic Science Center performs the autopsies on fentanyl deaths. Toxicology reports can take four to six months to complete, leading to a backlog in data reporting. (Polly Basore Wenzl/The Beacon)

Dozens of local teens have died from fentanyl

The Beacon asked the Sedgwick County Regional Forensic Science Center to break out the numbers of fentanyl-related deaths in people 18 and younger over the past three years. According to the center, one such death occurred in 2020, nine in 2021 and possibly 17 in 2022. Deaths are almost certainly continuing this year, but there are no hard numbers yet.

“The hardest part about this is that the statistics are so lagging,” said Terri Moses, head of security for Wichita Public Schools and the district’s point person on fentanyl response.

The uncertainty is due to a four- to six-month delay in toxicology reports, attributed to staffing shortages at the forensic center, the unique testing requirements for fentanyl, and ongoing equipment upgrades.

The center was able to provide The Beacon the names of 11 youth — ranging in age from 22 months to 18 years — whose deaths were attributed to fentanyl in 2022. (The toddler’s death is the subject of an ongoing criminal investigation, District Attorney Marc Bennett said.)

Their autopsy reports, which are public records, were provided by the 18th Judicial District Court. Another six cases of suspected fentanyl youth deaths are pending, according to Shelly Steadman, center director.

The official autopsy report for Isaac Sandoval, 18, who died one month before his graduation from Maize High School last year. His cause of death is listed as fentanyl toxicity, an accident. (Polly Basore Wenzl/The Beacon)

To protect the privacy of these families — none of whom referenced fentanyl in their children’s obituaries — The Beacon is using the name of only one youth whose family is sharing their son’s story. Even without names, details from the provided autopsy reports reveal what fentanyl deaths among youth look like.

Frequently, it looks like teens who may habitually use marijuana or alcohol retreating to their bedrooms to take pills they may or may not know contain a deadly amount of fentanyl. It looks like parents and grandparents trying to rouse them for work or school and finding them unresponsive, calling 911 and learning their child is dead.

Autopsy reports portray otherwise healthy young people — a few with scars consistent with self-harm — with toxicology reports revealing habitual drug use, more typically marijuana, but occasionally also oxycodone, cocaine or Xanax. Three reports showed the presence of naloxone (also known by the brand name Narcan), a drug used to reverse the effect of opioid overdose. It doesn’t always work.

Using the names from the 11 provided autopsies, The Beacon found obituaries online for all but one. The obits describe young people who attended at least a half dozen area high schools. Nine were male; two were female. They were white, Black and Hispanic. Their ages were 22 months, 14, 16, 17 and 18.

The obituaries had one universal element: grief-stricken families who loved their lost children.

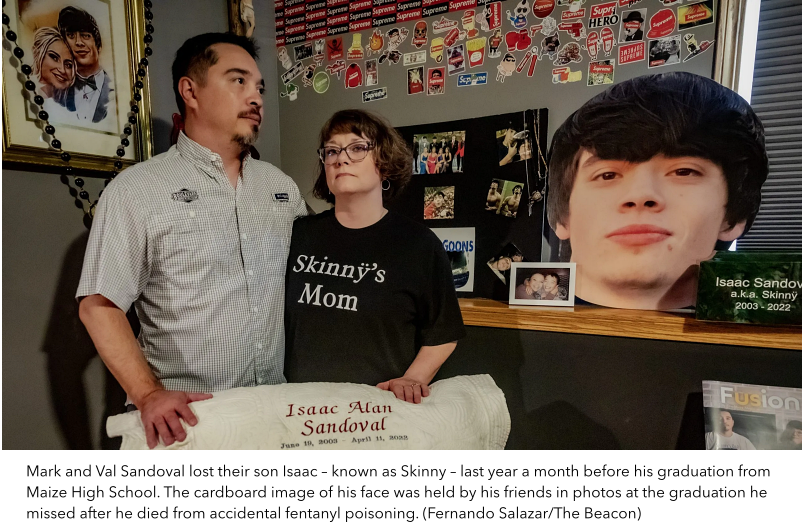

Val and Mark Sandoval share the story of finding their son Isaac – known as “Skinny” – dead in his bed a month before his graduation last year from Maize High School. The Sandovals spoke at a drug awareness assembly at Maize South High on April 28. (Polly Basore Wenzl/The Beacon)

Parents of Isaac ‘Skinny’ Sandoval share their story of loss

On the last night of his life, 18-year-old Isaac Sandoval stood at the end of his parents’ bed, his head purposely blocking their view of the television to command their full attention. Isaac told his dad, Mark Sandoval, that he was looking forward to shopping together the next day to buy clothes for his senior pictures. Isaac playfully teased them that he would pick out the most expensive outfits and shoes.

Isaac’s graduation from Maize High School was a month away. He had already completed the credits necessary to graduate, and since spring break had no longer needed to attend classes. Instead he was working to save money for an apartment with the girlfriend he’d just attended prom with, making plans to eventually pursue sports medicine or physical therapy as a career.

“He ended this conversation by hugging and kissing his mom goodnight,” said Mark Sandoval. He recounted their final conversation with their son to an auditorium filled with hundreds of teens at a schoolwide assembly at Maize South High on April 28. Several in the audience knew him because Isaac – known as “Skinny” – was a gregarious young man with friends at Maize, Maize South, Goddard, Valley Center and Northwest high schools.

The morning after that conversation and hug, Val Sandoval, Isaac’s mother, went to work. Mark went to Isaac’s bedroom to wake him. “It was always a chore waking him up,” Mark said. He found Isaac belly down, his face buried between two pillows, “not an unusual sleeping position for him.”

He turned on the light and called out, “Wakey! Wakey,” but heard not so much as a mumble or moan in reply. Mark left the room to fold some laundry, continuing to holler at his son. When he returned to Isaac’s room, he noticed bare skin peeking out from the blanket. It looked cold and blotchy. Mark asked Isaac if he was cold. After no response, he began to shake his son, then flipped him over.

Mark, a trained surgical nurse who is now a hospital administrator, did a quick assessment: Eyes fixed, pupils dilated, no heartbeat, no breathing. He called 911 and began CPR.

“The first responders knew what I already knew in my heart: Isaac had been gone for hours. There was absolutely no hope of reviving him,” Mark told his audience of high school students. There was no sound in the auditorium but his voice.

He would need to call his wife to come home. A co-worker drove her to the house. When she arrived, police were guarding the front door and would not let her see their son. “Our baby’s room is now being treated as a crime scene,” Mark said.

The Sandovals would learn that Isaac died from accidental fentanyl poisoning. He had taken what he thought to be a Percocet – an opioid painkiller – to help him sleep. The family pieced together what happened after Isaac’s sister unlocked his phone. He had met a dealer at a laundromat in south Wichita to buy four Percocet pills. The dealer offered him two free pills because he was running late.

Val told the audience: “The morning Isaac was discovered, the police found two pills in his bathroom. We found one in his wallet. Two of Isaac’s friends took a pill, and Isaac took the sixth pill. Those two friends woke up the next day. My baby did not.”

Isaac Alan Sandoval died on April 11, 2022. His autopsy lists the cause of death as fentanyl toxicity.

“I didn’t know anything about fentanyl until my son was found dead from it,” Val said in an interview after the assembly. She said she and her husband are speaking out as often as they can about the dangers of accidental fentanyl poisoning. They want to save kids’ lives and spare other parents their pain.

The Wichita Metro Crime Commission made these “One Pill Can Kill” posters available to all area high schools, public, private and parochial. This one appears near the entrance to Maize South High School. (Polly Basore Wenzl/The Beacon)

Teens and adults scramble to prevent more youth fentanyl death

The Sandovals believe more should be done to warn parents and protect teens from the dangers. Much is already being done. Efforts ramped up not long after the deaths of Isaac Sandoval and others in April 2022. But they may not be obvious to parents and other adults who haven’t seen fentanyl as a threat.

Erik Smith, an assistant administrator of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, also spoke at the Maize South assembly. Smith said the amount of fentanyl in circulation is too widespread for law enforcement to halt. The DEA seizes millions of pills every year, and six out of 10 contain a lethal dose of fentanyl.

“We’re not going to arrest our way out of this problem. We need to stop it at the prevention and education level,” Smith said.

In April 2022, Sedgwick County deputies started carrying Narcan, which can reverse the effects of opioid overdose, including fentanyl. In July 2022 the Wichita Police Department hosted a town hall on fentanyl at Wichita State University. The Sandovals spoke at the event.

In August, the Mental Health and Substance Abuse Coalition began meetings of a fentanyl task force, drawing in law enforcement, mental health and substance abuse providers, schools and harm-reduction specialists.

Safe Streets Wichita, a nonprofit advocating harm-reduction measures, began lobbying for Wichita Public Schools to have Narcan on-site. “That is something we worked on for quite a long time,” said Ngoc Vuong, a Safe Streets activist. The effort was successful.

Moses, the district’s security chief, said Wichita Public Schools approved making Narcan available in schools at the beginning of the 2022-23 school year, “but getting it and getting everybody trained took a little bit of time.” She estimates that by November Narcan was in place in multiple locations through each Wichita high school with nurses, security staff and administrators trained in its use.

Beyond that, Moses said the district hasn’t offered a formal fentanyl education program.

Drug education is typically taught in health classes as part of a broader curriculum centered on teaching teenagers to make good choices rather than ones that could jeopardize their futures.

Fentanyl has changed everything, Moses said. “Now you can lose your life immediately.”

The district did recently make available to all schools a video called “Song for Charlie,” which points out the risk of fake pills and includes a lesson plan to be done during what the district calls “advocacy time,” more commonly known as homeroom. “We wanted to provide facts so (teachers) could have discussions with students.”

The primary message: Don’t take anything that wasn’t prescribed by a doctor and dispensed to you by a pharmacy. Fentanyl could be in anything that comes from the street.

Moses said high schools throughout Sedgwick County have also placed “One Pill Can Kill” posters in school hallways. The posters were provided by the Wichita Metro Crime Commission. One such poster hangs in Maize South High, where the Sandovals recently spoke.

“I do like the ‘One Pill Can Kill’ campaign,” Mark Sandoval said. But because not every pill can kill, he thinks it’s important to help youth understand the statistics. “Your friend right next to you can live through it, but two others may die.”

Vuong, the harm reduction activist, said he has mixed feelings about the slogan. “There’s a lot more going on than the drug itself. The question I ask is, why are students using drugs in the first place? There’s a lot of self-medication going on.” Vuong wonders how the message “One Pill Can Kill” might influence a depressed teen with suicidal thoughts.

Teens, parents and others attend the April 29 premiere of “Riverside High,” a graphic-novel styled film initially produced to run installments on TikTok and in TeenView Magazine. The story centers on high school students grappling with the accidental fentanyl poisoning of a friend who is saved when another teen administers Narcan. The film was shown free at the Boulevard Theatres at Towne West Square mall as part of a F!ght Fentanyl public awareness event. (Fernando Salazar/The Beacon)

Teens take fight against fentanyl into their own hands

The most aggressive messaging efforts around fentanyl are being driven by teens. In Maize USD 266, students at Maize High and Maize South successfully pushed for assemblies. Teenagers in Wichita went further — creating a serialized comic called “Riverside High” that features teens confronting an accidental fentanyl poisoning.

The serial appears in TeenView Magazine, a monthly publication produced by teenagers in the Youth Educational Empowerment Program, which has clubs at West and South High. A video version has been released in installments on TikTok, and a complete series video runs about 30 minutes.

The creators wanted both the magazine and the video to be distributed throughout Wichita Public Schools. They were denied. “We reviewed the initial materials they created and found some of the content was not appropriate,” said Susan Arensman, Wichita Public Schools spokesperson.

Frustrated, six students addressed the Wichita school board’s Feb. 13 meeting, arguing that student-produced efforts were more likely to resonate with teens than what adults are doing.

“Sure I noticed the (One Pill Can Kill) poster at freshman orientation day, but it was just that to me. A poster,” Jeremiah Olguin, a Wichita South High freshman, told the school board. Olguin called posters “outdated” and urged districts to connect better with students. “USD 259 does not think the way their main demographic — kids — actually think.”

Lydia Harper, a senior at South High School, asked for the opportunity for teens to speak directly to their peers. “Our youth will not listen to adults and take them seriously because they never think it will happen to them until it does.”

“Riverside High” does have the support of the Sedgwick County Sheriff’s Department, the Wichita Police Department and the Wichita Metro Area Crime Commission, which are working in partnership with Teen View Magazine to support a broader “F!ght Fentanyl” campaign.

Wichita Police Chief Joe Sullivan and Sedgwick County Sheriff Jeff Easter have their photo taken together by TeenView Magazine organizers of the F!ght Fentanyl event April 29 at Towne West Square mall. (Courtesy photo/Dawn Cano, TeenView Magazine)

According to Dawn Cano, director of marketing for TeenView Magazine, those organizations and others are helping underwrite a $100,000 social media “F!ght Fentanyl” ad campaign directed at middle- and high-school youth.

The ads are appearing on TikTok, SnapChat, Spotify and Hulu, using geographic message targeting to reach students and their parents at their schools and homes. The campaign is ongoing but the biggest push will be the final two months of this school year and the first two months in the fall, according to Sharon Van Horn, crime commission executive director. In addition to the social media campaign, the crime commission has placed “One Pill Can Kill” billboards on Kellogg Avenue and digital signage of car dealerships.

Sheriff Jeff Easter and Wichita Police Chief Joe Sullivan showed up on April 29 to support the premiere of “Riverside High” at a free showing at Towne West Square mall, part of a F!ght Fentanyl event.

“We believe in our youth and what our youth is trying to do for our youth, and we have got to change what’s going on in this community,” Easter told the audience before the film began.

The event also attracted Sedgwick County commissioners Sarah Lopez and David Dennis and Wichita school board member Kathy Bond. Bond said the issue is of personal importance to her because she has a friend whose 20-year-old son died of accidental fentanyl poisoning.

Her friend found her son dead in his bed at home.

This article first appeared on The Wichita Beacon and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

![]()

—

***

You Might Also Like These From The Good Men Project

Compliments Men Want to Hear More Often Compliments Men Want to Hear More Often |

Relationships Aren’t Easy, But They’re Worth It Relationships Aren’t Easy, But They’re Worth It |

The One Thing Men Want More Than Sex The One Thing Men Want More Than Sex |

..A Man’s Kiss Tells You Everything ..A Man’s Kiss Tells You Everything |

Join The Good Men Project as a Premium Member today.

All Premium Members get to view The Good Men Project with NO ADS.

A $50 annual membership gives you an all access pass. You can be a part of every call, group, class and community.

A $25 annual membership gives you access to one class, one Social Interest group and our online communities.

A $12 annual membership gives you access to our Friday calls with the publisher, our online community.

Register New Account

Log in if you wish to renew an existing subscription.

Username

First Name

Last Name

Password

Password Again

Choose your subscription level

- Yearly – $50.00 – 1 Year

- Monthly – $6.99 – 1 Month

Credit / Debit Card PayPal Choose Your Payment Method

Auto Renew

Subscribe to The Good Men Project Daily Newsletter By completing this registration form, you are also agreeing to our Terms of Service which can be found here.

Need more info? A complete list of benefits is here.

—

Photo credit: Fernando Salazar/The Beacon

The post A Surge in Fake Pain Pills Is Fueling a Deadly Epidemic Among Wichita’s Teens appeared first on The Good Men Project.