Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy — then, now and the hidden pioneers

Have you heard of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy? No? Neither had the world of cardiology until it was coined by John Goodwin and his team in the 1950s. Today, we know more about this disease than ever, thanks to BHF pioneers and current BHF-funded research.

What is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy?

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a disease that causes the muscle walls of the heart’s left side to thicken, making it harder to pump blood around the body. The muscle cells of the heart don’t align as they should — they are in disarray — and this can cause serious arrhythmias that can then lead to sudden cardiac arrest - the ultimate medical emergency where the heart stops beating and blood stops flowing around the body to the major organs. HCM affects 1 in 500 people in the UK and often shows no symptoms.

The BHF have supported the largest ever study of children with HCM. This project aims to develop a way to predict how HCM will develop. The results could save and improve lives across the UK. We owe much of this current success to the inspiring cardiologists who have worked hard to identify HCM many years ago as a specific disease.

The BHF has funded research into HCM for decades. Today, we’re fine tuning new ways to diagnose and treat this potentially devastating disease.

The hidden HCM Pioneers:

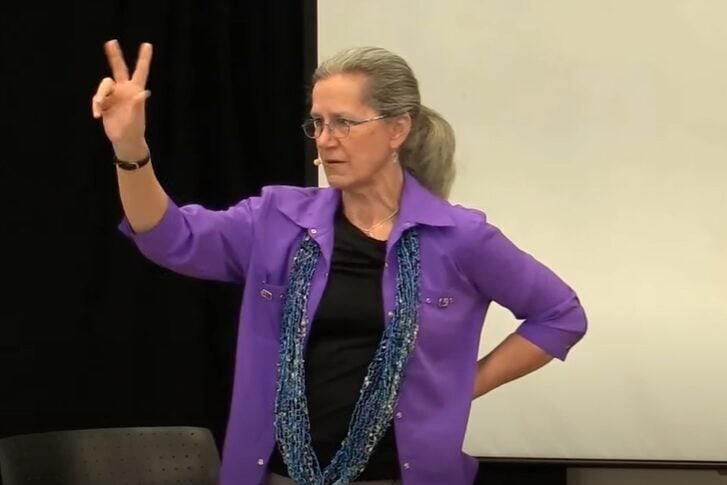

The term hypertrophic cardiomyopathy was established by a team led by Professor John Goodwin. Within his team was Professor Celia Mary Oakley, less visible in the history books, but undoubtedly a driver of success in early HCM research. In 1958 Oakley was one of just three female cardiologists in the UK, and the first woman to be appointed house surgeon for Dr Paul Wood at the Royal Brompton Hospital. Oakley researched high blood pressure and congenital heart disease and she is considered one of the most outstanding cardiologists of her time. She assisted in a number of inspiring and innovative roles within cardiology, which include being appointed as personal chair at Hammersmith Hospital and founding fellow of the European society of Cardiology.

‘’ I had developed interests in a lot of niche areas and at the Hammersmith, I was sent a lot of weird and interesting cardiology cases’’- Celia Mary Oakley

Professor Celia Mary Oakley. Image: AHA Journal.

Professor Celia Mary Oakley. Image: AHA Journal.Research into the then ‘mysterious’ disease of HCM was not the only struggle Oakley faced in Cardiology. When applying for her first job as house surgeon for Paul Wood at the Brompton Hospital, Oakley enquired whether she would have a chance at being considered but was told that she would not be recommended as the job should not go to a woman. She decided to ask Paul Wood directly and was appointed. Later, Oakley was blocked in an attempted move to a new hospital as a consultant refused to work with a woman- she remained at Hammersmith Hospital where her innovative research thrived. The BHF funded Oakley for 5 years in the 1960s to study congenital heart disease in children before non-paediatric doctors were prevented from carrying out this kind of work.

“Because of my wide interests, an awful lot of interesting patients from all over the world came to see me,” she said in an interview for the scientific journal, Circulation.

Without the determined minds of Oakley and Goodwin, it’s likely our understanding of HCM would be very different.

Continuous curiosity led BHF Professor Michael Davies to be one of the first scientists to carry out studies on people who had died of HCM to see if anything else in the body could offer an insight into the underlying mechanisms.

In the 1990s, BHF funded researchers Bill Mckenna and BHF Professor Hugh Watkins were then among the first to find a faulty gene that could be the cause of some cases of HCM. The BHF have funded Professor Watkins since 1990 for his ongoing research into HCM causes, detection and treatment. Research has shown that some cases of HCM can be caused by a change or mutation in one or more genes that can be passed on through families. Each child of someone with HCM has a 50% chance of inheriting the condition themselves, but due to strides in research these faulty genes can sometimes now be recognised before symptoms appear.

“BHF support has been the backbone of my research career from the beginning”- Professor Hugh Watkins

Where are we now?

Although childhood HCM is rare, it is more likely to present during a growth spurt. Childhood HCM is an area of cardiology that has been relatively unchanged for the last two decades - making this BHF funded study a valuable contribution to the field.

The study ran across 17 countries until 2017, monitoring just over 1000 young people aged 16 years or younger with HCM. Using information that was already accessible from hospital records, researchers were able to create a model that can help estimate which patients had a 5 year risk of dying from sudden cardiac death.

The model can help map out the next 5 years and be able to see if the young person with HCM will be likely to need more or less medical attention as the years go on. This could help to guide doctors on future medical treatments.

BHF-funded research like this allows us to learn more about childhood hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and to understand better which patients are more at risk of developing more serious complications or conditions in future so they can receive the best preventative treatments available.

Miles Frost, the son of Sir David and Lady Carina Frost, died suddenly at the age of 31 from undiagnosed HCM, despite being an otherwise healthy and active adult. His family have now partnered with the BHF in creating ‘The Miles Frost Fund’ to raise money for genetic testing so that more people can be aware of the condition and get tested for faulty genes.

Research into HCM has made huge strides when it comes to understanding the disease, prevention and risk. The BHF also recognises the huge input made by Professor Celia Mary Oakley in a time when it was difficult for women to join the world of science.

Today, cardiology remains a male-dominated arena, with women making up 27% of cardiology trainees and just 14% of cardiology consultants in the UK. The BHF are aiming to close this gap by supporting women to succeed in research. For example, the BHF Daphne Jackson Fellowship and the Career Re-entry Fellowship help researchers to return to research after a career break. We must continue Oakley’s legacy not only when it comes to inspiring research, but inspiring women in the mission to end heartbreak for everyone.

If you like this, you might also like:

- “You can get left out a lot” — children share their experiences of having congenital heart disease

- Predicting the future for adults who were born with congenital heart disease

- Who run this research?

And follow the BHF publication on Medium

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy — then, now and the hidden pioneers was originally published in British Heart Foundation on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Original Article