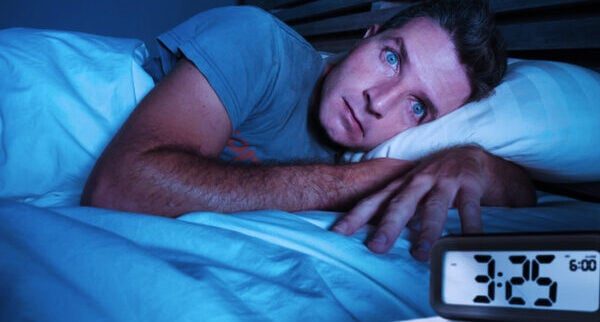

The DoD faces a unique challenge when it comes to PTSD treatment: Not only can troops experience combat-related trauma, but they also face long wait times and limited access to care. This means that in many cases, treatment begins too late for patients who are already struggling with symptoms like anxiety, depression or insomnia.

The Department of Defense (DoD) spends $2.5 billion annually to treat post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and mild traumatic brain injury (TBI). But treatment wait times are too long, and our heavily centralized system was designed for an era before the internet.

The Military Applications Group at MITRE is working with the DoD to attack this problem by developing innovative technology that can enable self-care for troops. In addition to a web interface and mobile apps, they’re working with Google’s DeepMind to build a virtual agent that simulates human interaction and can help troops ease new symptoms or check in on their progress.

The goal is to create a system that can help identify when soldiers are at risk of developing PTSD and provide them with cognitive therapy. This will allow the DoD to improve access, reduce costs and save lives.

The system works by scanning soldiers’ brains for neural activity associated with PTSD symptoms like anxiety, depression and anger. The machine learning algorithms are then trained to recognize these patterns in a way that is similar to how doctors diagnose patients. In addition, the system can also provide cognitive therapy by asking soldiers questions about their symptoms and offering suggestions for how they might be able to reduce their stress levels.

The project is currently in the testing phase and has not yet been deployed in the field. The system will be tested in a clinical trial involving around 400 soldiers. The goal is to compare how well it performs against traditional methods of diagnosing PTSD and providing therapy.

Image by iStockPhoto.com

The military’s battlefields have changed throughout history, but humans haven’t evolved much in the last 50,000 years. That means that modern combat scenarios still create powerful reactions in our brains and bodies because they resemble ancient life-or-death survival situations. In short, the brain is a complex organ. While some people are more prone to PTSD than others, it’s not something that can be “cured” like a disease. Instead of trying to wipe out the disorder entirely, military researchers hope that they can learn how to help troops cope with it — and even prevent some cases by exposing soldiers to virtual reality experiences before they go into combat to better inform the virtual agent’s learning.

A few hours of combat can trigger a cascade of physiological changes — heart rate increases, breathing speeds up, pupils dilate — that prepare us for fight or flight as adrenaline surges through our bloodstream. If this reaction leads to death or injury out on the battlefield, there’s no need for follow-up care; if not, we can relax again once the danger’s passed. Our bodies switch back to “normal mode.” All is well that ends well.

The body’s reaction to combat is different from its reaction to trauma, which is different from its response to PTSD, which is different from the body’s reaction to TBI, and so on. As you read this section, keep in mind that these terms are not interchangeable — they’re distinct and complex issues that require specialized treatment. For example:

◉ Trauma refers specifically to events such as a car accident or violent assault; it can also refer more broadly to any kind of violation or loss — for instance, when someone loses their home and family due to natural disaster or war.

◉ PTSD has been defined as “a group of symptoms” (American Psychological Association). The most common symptoms include flashbacks about the event; avoiding places or people associated with the event; feeling emotionally numb; and having nightmares about it.

◉ TBI occurs when there’s damage within the brain itself after an injury outside the skull — for example if someone falls off an ATV while riding through woods.

◉ Stress causes physical changes like increased blood pressure and heart rate — and psychological ones too: depression, anxiety

Image by iStockPhoto.com

We’ve been studying the brain for many years now; we know that certain regions activate when we’re stressed or afraid (the amygdala) and trigger our fight-or-flight survival instincts (the hypothalamus). We also know why these reactions are stronger in people who have experienced trauma: because our brains evolved over thousands of years in an environment where danger was everywhere; predators were always waiting for us behind every tree or rock. Our ancestors could never predict when danger would strike next and had to constantly keep themselves on high alert just in case — which means that today’s veterans often display similar patterns of behavior.

The bad news is that we don’t yet know how to control our reactions when we’re stressed out, so the best we can do is try to manage them. That’s where VR comes in, again: by helping people become more aware of their emotions and sensations, it may help them respond more calmly during stressful situations.

Using VR as the virtual agent’s guide to treating PTSD offers many benefits over traditional therapies. For one thing, the VR allows users to experience events from different perspectives (like when soldiers see themselves through the eyes of their peers); this helps them develop more empathy for other people. Also, VR can be used anytime and anywhere — so if you’re feeling stressed out at work or home, you can simply slip on your headset and relax before things get out of control. The more VR’s used, the more the virtual agent can learn, and the closer we’ll be able come to consistently treating PTSD with precision and success.

—

This post was previously published on medium.com.

***

You may also like these posts on The Good Men Project:

White Fragility: Talking to White People About Racism

White Fragility: Talking to White People About Racism  Escape the “Act Like a Man” Box

Escape the “Act Like a Man” Box  The Lack of Gentle Platonic Touch in Men’s Lives is a Killer

The Lack of Gentle Platonic Touch in Men’s Lives is a Killer  What We Talk About When We Talk About Men

What We Talk About When We Talk About Men —

Photo credit: iStockPhoto.com

The post Why the US Military Is Building a Cognitive Virtual Agent and investing in VR to Help Troops with PTSD appeared first on The Good Men Project.

Original Article